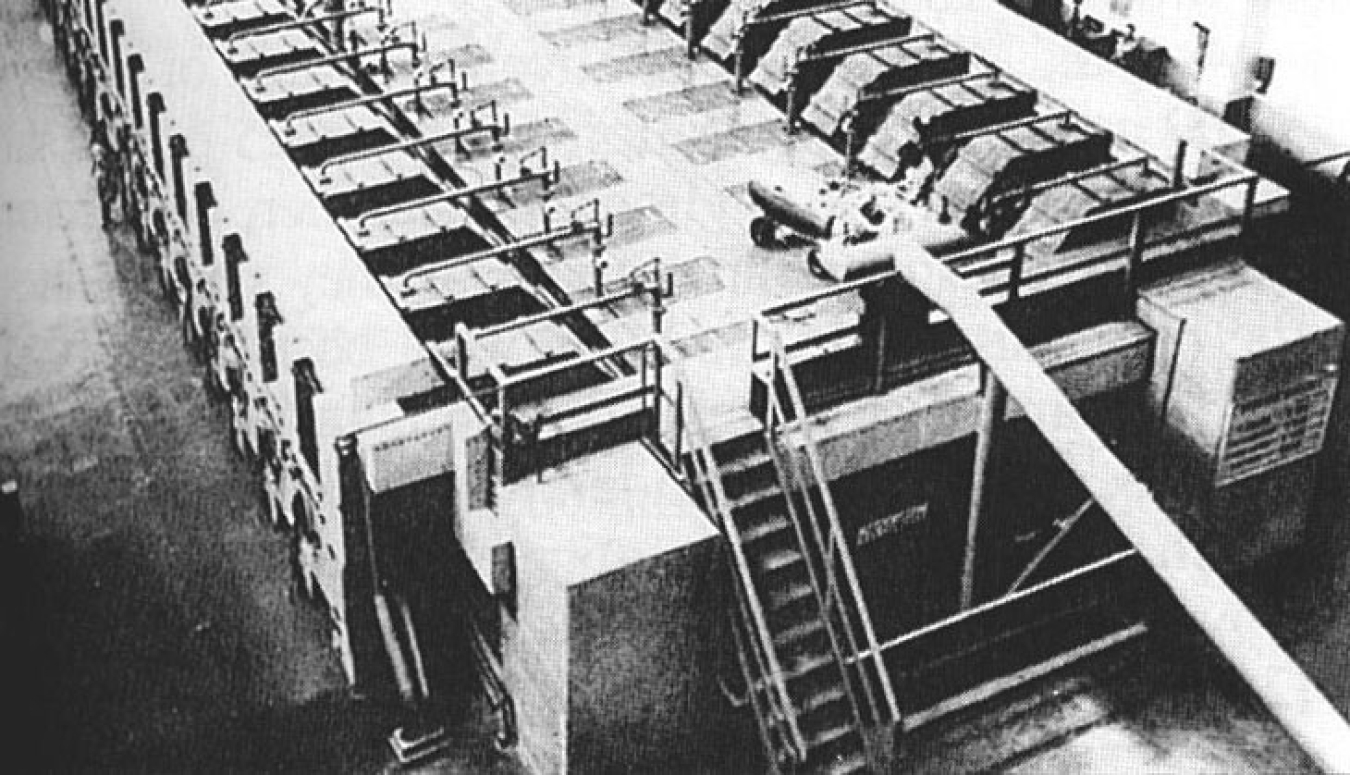

Built near the northeastern end of the Oak Ridge reservation, the Y-12 facility used the electromagnetic method to separate uranium-235 from the uranium-238 in natural uranium. During the Manhattan Project, Y-12 housed nine Alpha and eight Beta racetracks, which were arrangements of huge electromagnets containing a number of calutrons in the magnets' gaps. The calutrons sent a stream of charged particles through the magnetic field, deflecting the atoms of the lighter isotope more than those of the heavier isotope. This resulted in two streams that could be collected in different sections of the receivers. Containing 96 calutron tanks, each Alpha track was 122 feet long, 77 feet wide, and 15 feet high. Beta tracks were smaller, in a rectangular rather than the oval configuration of the Alphas, and contained 36 tanks each. Like K-25's gaseous diffusion method, Y-12's electromagnetic method was an entirely new technology.

The racetracks required extraordinary amounts of copper for magnet windings. As copper was badly needed for the war effort, the Manhattan Engineer District borrowed as a substitute almost 15,000 tons of silver bullion from the United States treasury to fabricate into strips and wind on to coils. Construction of the plant began in February 1943, and the first Alpha calutron ran in January 1944. The Alphas provided partially enriched feed for the Betas. In early 1945, the K-25 and S-50 facilities began supplying slightly enriched feed for the Alphas. The final product of highly enriched uranium (uranium-235) for the Hiroshima weapon came from the Betas. All nine Alphas and six of the Betas had been dismantled by the end of 1946 when gaseous diffusion became the sole process for enriching uranium. The Y-12 Beta-3 racetracks are the only surviving production equipment from the electromagnetic isotope separations process.