Imagine if the same mold that ruins old grapes and onions could double as a key ingredient in the recipe to reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory are working to harness the natural process that spoils fruits and v...

June 21, 2011

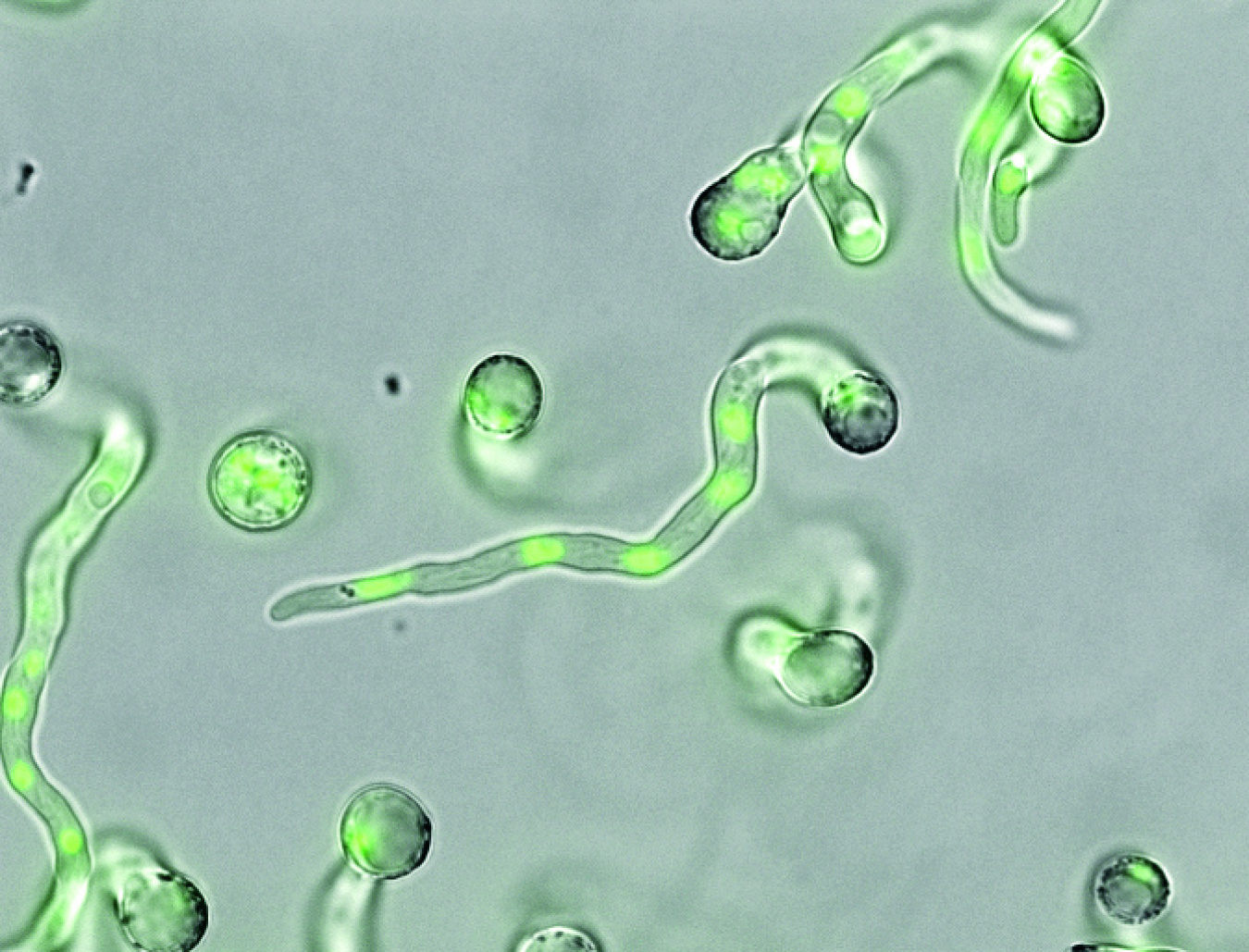

A view of Aspergillus niger with the fungus’ DNA highlighted in green | Photo Courtesy of: PNNL.

Nobody likes opening a fridge to find food that’s spoiled, but imagine if the same mold that ruins old grapes and onions could double as a key ingredient in the recipe to reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil. It’s an outcome much less imaginary than you might think, thanks to Energy Department research on the common fungus Aspergillus niger. Scientists at the Department’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) are working to harness the natural process that spoils fruits and vegetables as a way to make fuel and other petroleum substitutes from the parts of plants that we can’t eat.

An international team of researchers led by PNNL’s Scott Baker recently completed a study that compared the genome sequences of two strains of Aspergillus niger -- the ubiquitous “wild type” that’s a kitchen nuisance and the type commonly used to make valuable enzymes for the food and drug industries. The Department’s Joint Genome Institute completed the sequence for wild type, the first of nearly a dozen additional Aspergillus strains used in industry that the Institute plans to sequence. “Learning more about the genetic bases of the behaviors and abilities of these two industrially relevant fungal strains will allow researchers to exploit their genomes towards the more efficient production of organic acids and other compounds, including biofuels,” wrote Baker and his colleagues in the paper.

This isn’t the first time we have turned to Aspergillus niger for an organic solution to a national dilemma. The fungus first came into industrial use in response to a disruption in the citrus fruit supply from the Mediterranean and the United States caused by World War I. Prior to that time, citric acid – a natural preservative in items ranging from soda to cleaning products – was made chiefly from Italian lemons. In response to the wartime shortage of citrus, the drug company Pfizer developed an industrial process that used fungus to produce citric acid. By the late 1920’s, citric acid from Aspergillus niger had completely displaced the fruit-derived version. Today more than a million tons of citric acid – nearly all the world’s supply – is produced this way every year.

Having already proven itself what Baker terms an "industrial workhorse," Aspergillus niger now shows great potential to again reduce our dependence on foreign imports … this time, on crude oil. Baker sums it up this way: “We know that this single organism is used for production of organic acids and for enzymes, and it can degrade plant cell wall matter for sugar production. For biofuels it's a highly relevant organism since it's already been scaled up, shown to be safe and used for organic acids production.”

The Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy's Biomass Program provides funding for PNNL’s fungal biotechnology research and played a key role in coordinating the international collaboration for this study. The Energy Department’s investments to pioneer innovative pathways to biofuel alternatives -- like the kind being studied at Pacific Northwest National Lab -- form a key part of the Department’s broad strategy to ensure commercially viable, domestically-produced and sustainable alternatives to foreign oil.